Every enterprise codebase has a couple classes nobody wants to touch, those with thousands of lines of code and complex business logic definitions buried in if/else statements.

Fortunately, there's a way to fix this without a major refactor. And if you have ever watched Dragon Ball you already understand it: Capsules.

Bulma and Capsule Corporation created these incredible capsules that could store anything: cars, houses, entire laboratories. Press the button, and poof, out comes whatever was stored inside. Need a motorcycle in the middle of nowhere? Throw a capsule. Want to set up camp? There's a capsule for that.

The person using the capsule doesn't need to know how it works, they don't need to understand the compression technology or the physics. They just need to know how to press the button and throw it, the rest magic.

Command pattern: encapsulate an action and its dependencies as an object that can be stored, passed around, and executed on demand.

Three rules make a capsule work:

- Self-contained. Everything needed is inside, whether that's a single motorcycle or an entire house with plumbing and electricity.

- Uniform trigger. Every capsule has the same button mechanic to activate them.

- User stays decoupled. Goku doesn't need to understand compression physics to set up camp.

Now look at a typical controller:

public class OrderController

{

public void HandleRequest(string action, Order order)

{

if (action == "submit")

{

_validator.Validate(order);

_inventory.Reserve(order.Items);

_db.Save(order);

_emailService.SendConfirmation(order);

}

else if (action == "cancel")

{

_inventory.Release(order.Items);

_paymentService.Refund(order);

_db.Update(order);

_emailService.SendCancellation(order);

}

else if (action == "expedite")

{

_paymentService.ChargeExpedite(order);

_warehouse.PrioritizeShipment(order);

_db.Update(order);

}

// and it keeps growing...

}

}Each action has its own dependencies and logic, but they're tangled together. Adding "expedite" meant understanding everything else. Changing "cancel" risks breaking "submit."

Mapping it to the enterprise

What if each action was its own capsule?

That's exactly what the Command pattern does. It takes each action, bundles it with everything it needs to execute, and wraps it behind a uniform interface. The caller no longer needs to knows how to submit, cancel, or expedite, It just needs to know how to execute a command.

Same as with capsules, we separate the implementation and the necessary dependencies from the caller.

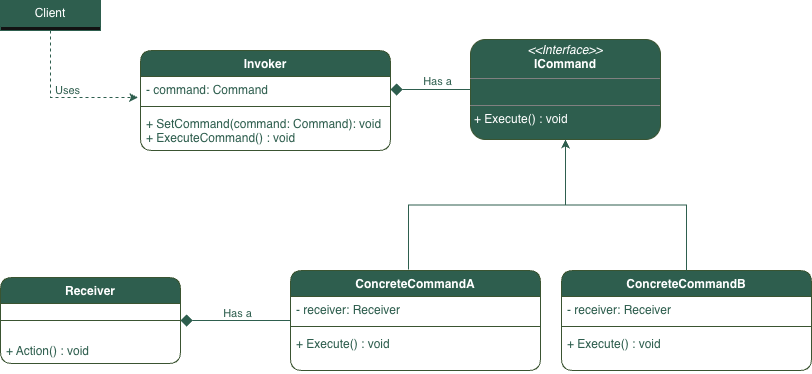

Bellow is the formal class diagram and role definition

| Component | Role |

|---|---|

| Command | The encapsulated behavior bundling orchestration and dependencies |

| Receiver | Object dependencies that the command object needs |

| Invoker or dispatcher | Triggers the command execution |

| Client | User of the invoker |

The Code

Now, let's translate this to our order system sample.

- A request comes in to submit an order.

- The Client (a controller) creates a

SubmitOrderCommand, passing in the order and all the Receivers it needs: validator, inventory service, repository, email service. - Then the Client hands the command to the Invoker, which calls

Execute(). - The Invoker doesn't know what's inside or what will happen. Inside

Execute(), the Command orchestrates the Receivers: validate, reserve inventory, save, send confirmation.

The controller never touches business logic, the command doesn't know who calls it and the invoker doesn't know the details or dependencies of the commands inner workings. Each piece has one single job.

Here's what that looks like in code.

public interface ICommand

{

void Execute();

}// Concrete Command: bundles the action and its dependencies

public class SubmitOrderCommand : ICommand

{

private readonly Order _order;

private readonly IValidator _validator;

private readonly IInventoryService _inventory;

private readonly IOrderRepository _repository;

private readonly IEmailService _email;

public SubmitOrderCommand(

Order order,

IValidator validator,

IInventoryService inventory,

IOrderRepository repository,

IEmailService email)

{

_order = order;

_validator = validator;

_inventory = inventory;

_repository = repository;

_email = email;

}

public void Execute()

{

// Receivers: The command object's dependencies needed to perform the work

_validator.Validate(_order);

_inventory.Reserve(_order.Items);

_order.Status = OrderStatus.Submitted;

_repository.Save(_order);

_email.SendConfirmation(_order);

}

}public class CancelOrderCommand : ICommand

{

private readonly Order _order;

private readonly IInventoryService _inventory;

private readonly IPaymentService _payment;

private readonly IOrderRepository _repository;

public CancelOrderCommand(

Order order,

IInventoryService inventory,

IPaymentService payment,

IOrderRepository repository)

{

_order = order;

_inventory = inventory;

_payment = payment;

_repository = repository;

}

public void Execute()

{

_inventory.Release(_order.Items);

_payment.Refund(_order);

_order.Status = OrderStatus.Cancelled;

_repository.Save(_order);

}

}// Invoker (or Dispatcher): triggers commands without knowing their details

public class CommandInvoker

{

public void Execute(ICommand command)

{

try

{

command.Execute();

}

catch(Exception ex)

{

Console.WriteLine($"Command failed with message {ex.Message}")

}

}

}Usage:

// Client: creates and configures the command

var order = new Order { Id = "123", Items = items };

var submitCommand = new SubmitOrderCommand(

order, validator, inventory, repository, email);

// Invoker just calls Execute()

var invoker = new CommandInvoker();

invoker.Execute(submitCommand);Spoiler: You've Already Been Using This

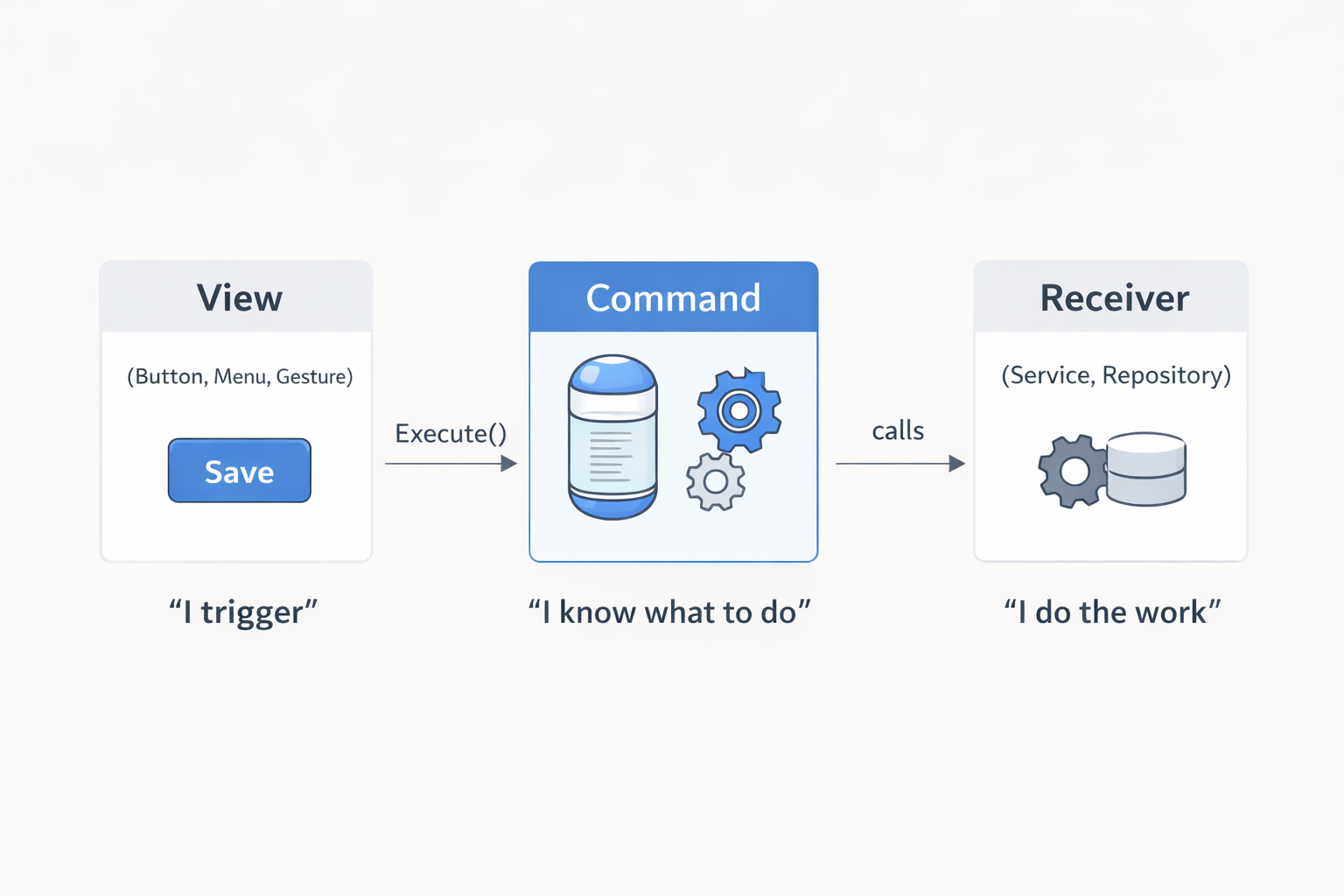

If you've built applications with WPF, .NET MAUI, Xamarin, or Android, you've likely used the Command pattern without naming it.

These frameworks embrace architectures like MVVM (Model-View-ViewModel) and MVP (Model-View-Presenter), where views never call business logic directly. Instead, they bind to commands: self-contained actions that execute when a user clicks, taps, or triggers an interaction.

The view knows that something should happen. The command knows what should happen. Neither knows about the other's internals.

<Button Text="Save" Command="{Binding SaveCommand}" />SaveCommand = new RelayCommand(async (DocumentService documentService) =>

{

await documentService.SaveAsync(_currentDocument);

});At first glance, this looks nothing like the SubmitOrderCommand we built earlier but the command is still there, just a bit more implicitly:

- Command. The SaveCommand variable that holds the implementation details

- ConcreteCommand. The lambda body definition containing the actual code

- Receivers.

documentServiceand any other dependency passed or shared. - Invoker. The view is the implicit invoker, reacting to user input.

Same three rules: self-contained logic, uniform trigger, caller stays decoupled.

When to use?

Good fit:

- The same action gets triggered from multiple places

- You need to execute logic before or after the command

- You need consistent logging or telemetry across actions

- Undo and redo are on the roadmap

- Actions need to be queued or executed asynchronously

- Testable isolated components

Not worth it:

- Two or three stable actions that rarely change

- No need to separate dependencies from the calling code

- No need for pre or post execution logic

- The abstraction costs more than the flexibility it provides

The Tradeoff

The Command pattern trades immediate simplicity for structured flexibility. In return, you get isolated actions that are testable, extensible without risk, and composable with infrastructure like logging, queuing, and undo.

The question becomes: "Is my requirement complex enough that it compensates the added architecture?"

Production optimizations

Pre or post code execution

You can have your invoker execute code before or after calling the command object, behaviors such as logging, telemetry, error handling, queuing, etc. For cases with a more complex pipeline could trigger a Chain of Responsibility, but that's a topic for another day.

Below is a simple sample adding logging and a try/catch mechanism in the invoker, giving this behavior for free to all available commands.

public class LoggingInvoker

{

private readonly ILogger _logger;

public void Execute(ICommand command)

{

var name = command.GetType().Name;

_logger.LogInformation("Executing {Command}", name);

try

{

command.Execute();

_logger.LogInformation("Completed {Command}", name);

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

_logger.LogError(ex, "Failed {Command}", name);

throw;

}

}

}Undo

Commands can be reversible by implementing the reverse operation in an Undo() method.

public interface IUndoableCommand : ICommand

{

void Undo();

}

public class SubmitOrderCommand : IUndoableCommand

{

// ... constructor and fields ...

public void Execute()

{

_validator.Validate(_order);

_inventory.Reserve(_order.Items);

_order.Status = OrderStatus.Submitted;

_repository.Save(_order);

}

public void Undo()

{

_inventory.Release(_order.Items);

_order.Status = OrderStatus.Draft;

_repository.Save(_order);

}

}This works when undo logic is straightforward: release what you reserved, revert a status, delete what you created. When state changes span multiple entities or require capturing an object's full snapshot before modification, the Memento pattern is a better fit.

Testing

Each command is a unit with clear boundaries:

[Fact]

public void SubmitOrderCommand_ReservesInventory()

{

var order = new Order { Id = "123", Items = items };

var inventory = new Mock<IInventoryService>();

var command = new SubmitOrderCommand(

order, validator, inventory.Object, repository, email);

command.Execute();

inventory.Verify(i => i.Reserve(order.Items), Times.Once);

}Summary

The Command pattern packages actions as objects, bundling logic and dependencies so they can be stored, passed around, and executed on demand.

Remember the capsules: self-contained, uniform trigger, user decoupled from complexity. That's the mental model.

The advantage: actions become testable units, new actions mean new classes instead of longer switch statements, and infrastructure like logging, queuing, and undo layers on top without touching the actions themselves.

The cost: more classes to navigate and upfront setup. For simple CRUD, direct calls are clearer. For complex workflows with cross-cutting concerns, the structure pays for itself.