We have all dealt with status checks distributed between method and classes. What started as a simple if (status == Draft) becomes a nested maze of conditions nobody wants to deal with.

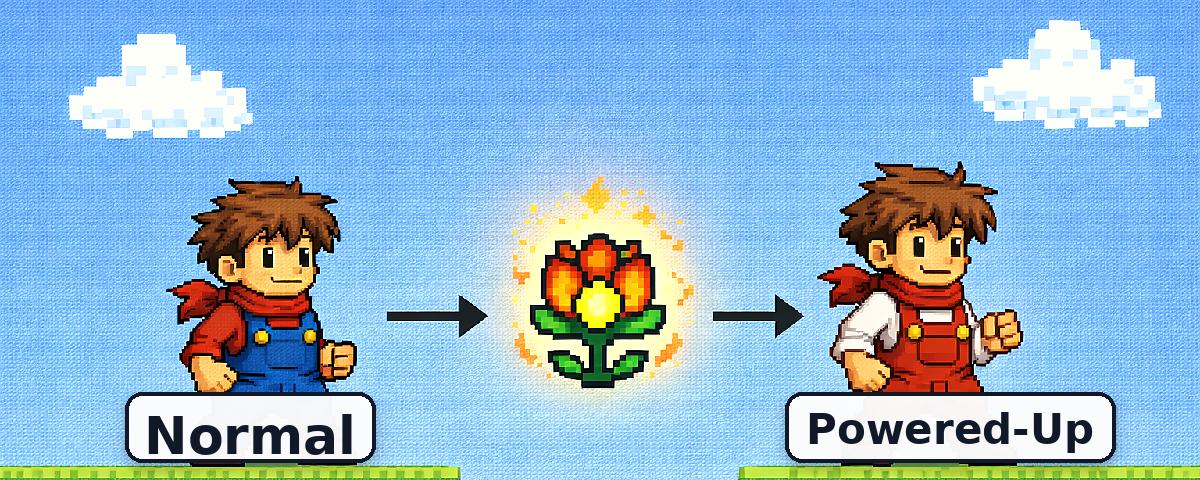

Fortunately, there's a way to organize this chaos. And if you've ever played Super Mario, you already understand it : Power-ups.

Throughout the game, you use the same controller, the same jump button, the same action button. But what happens when you press those buttons changes completely based on items you can pick up called power-ups.

When Mario grabs a Fire Flower, he transforms into Fire Mario. He looks different, but more importantly, he behaves differently. As Fire Mario the action button throws a fire ball while as regular Mario you would run.

Same input, same interface, completely different behavior.

And what about damage? As Fire Mario you take damage and go back to Super Mario and with another hit you go to regular (small) Mario. The system takes care of these transition rules

State pattern: encapsulate state-specific behavior into separate objects, letting an entity change how it behaves when its internal state changes.

Three things make Mario's power-up system work:

- Uniform interface. The controls never change regardless of power-up, their action does.

- Self-contained behavior. Each power-up knows what it can do.

- Explicit transitions. There's a specific way to go between power ups. Fire Mario cannot go to normal (small) Mario directly.

Now look at a typical service method:

public class OrderService

{

public void ProcessOrder(Order order)

{

if (order.Status == OrderStatus.Draft)

{

_validator.Validate(order);

_inventory.Reserve(order.Items);

order.Status = OrderStatus.Submitted;

_repository.Save(order);

_emailService.SendConfirmation(order);

}

else if (order.Status == OrderStatus.Submitted)

{

_paymentService.Charge(order);

order.Status = OrderStatus.Paid;

_repository.Save(order);

}

else if (order.Status == OrderStatus.Paid)

{

_warehouse.Ship(order);

_inventory.Commit(order.Items);

order.Status = OrderStatus.Fulfilled;

_repository.Save(order);

}

else if (order.Status == OrderStatus.Fulfilled)

{

throw new InvalidOperationException("Order already fulfilled");

}

// and it keeps growing...

}

}Each status has its own behavior and dependencies, but they're tangled together. Adding "Refunded" means understanding everything else.

Mapping It to the Enterprise

What if each status was defined as its own behavior?

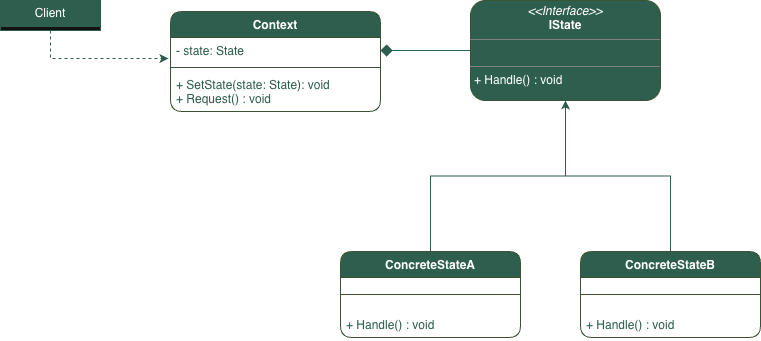

That's exactly what the State pattern does. It takes each status, bundles its behavior and transition rules into a dedicated class, and wraps it behind a uniform interface. The caller no longer needs to know how to process draft, submitted, or paid orders. It just needs to know how to call Process().

Same as with power-ups, we separate the behavior and transition logic from the entity that holds the state.

Below is the formal role definition:

| Component | Role |

|---|---|

| State | The behavior for a specific status |

| Context | The subject, the one holding the states and triggering their actions. |

| Client | Uses the context without knowing which state is active |

The Code

Now, let's translate this to our order system sample.

- A request comes in to process an order.

- The Context (

Order) holds a current state, starting withDraftState. - When

Process()is called, the Order delegates to whatever state it currently holds. - The State executes its behavior and transitions the Order to the next state.

- The next time the same order comes and executes again, the state will be different resulting in a different behavior

Here's what that looks like in code.

// State Interface

public interface IOrderState

{

void Process(Order order);

}// Context: holds current state, delegates actions

public class Order

{

public string Id { get; set; }

public List<OrderItem> Items { get; set; }

private IOrderState _state;

public Order()

{

_state = new DraftState();

}

public void SetState(IOrderState state) => _state = state;

public void Process() => _state.Process(this);

}// Concrete State: bundles behavior and transition logic

public class DraftState : IOrderState

{

private readonly IValidator _validator;

private readonly IInventoryService _inventory;

private readonly IOrderRepository _repository;

private readonly IEmailService _email;

public DraftState(

IValidator validator,

IInventoryService inventory,

IOrderRepository repository,

IEmailService email)

{

_validator = validator;

_inventory = inventory;

_repository = repository;

_email = email;

}

public void Process(Order order)

{

_validator.Validate(order);

_inventory.Reserve(order.Items);

_repository.Save(order);

_email.SendConfirmation(order);

order.SetState(new SubmittedState(_payment, _repository));

}

}// Another Concrete State

public class SubmittedState : IOrderState

{

private readonly IPaymentService _payment;

private readonly IOrderRepository _repository;

public SubmittedState(

IPaymentService payment,

IOrderRepository repository)

{

_payment = payment;

_repository = repository;

}

public void Process(Order order)

{

_payment.Charge(order);

_repository.Save(order);

order.SetState(new PaidState(_warehouse, _inventory, _repository));

}

}Usage:

var order = new Order { Id = "123", Items = items };

order.Process(); // DraftState: validates, reserves, transitions to Submitted

order.Process(); // SubmittedState: charges payment, transitions to Paid

order.Process(); // PaidState: ships, transitions to FulfilledNote on transition ownership: In this example, each state controls its own transitions. You can also centralize transition rules in the Context, or extract them into a dedicated transition manager. The right choice depends on how complex your rules are.

When to Use?

Good fit:

- Behavior changes based on an object state

- Transition rules are important and complex.

- You're seeing

if (status == X)scattered across multiple files - Adding a new status means editing multiple places

- Is not easy to determine all the business rules affected by a single state change.

Not worth it:

- You have 2-3 simple, stable states.

- Behavior differences are trivial.

- Transition rules are simple or non-existing.

- A straightforward switch statement is clearer.

The Tradeoff

The State pattern trades immediate simplicity for structured flexibility. In return, you get isolated state behaviors that are testable, transitions that are explicit, and business logic that is easier to follow up regardless of complexity.

The question becomes: "Are business rules around states and their transition complex enough that it would compensates the added architecture?"

Production Optimizations

Atomic Transitions

We can enforce all action within a state behavior to either succeed or fail together, as we would with database transations.

public class SubmittedState : IOrderState

{

public void Process(Order order)

{

using var transaction = _repository.BeginTransaction();

_payment.Charge(order);

order.SetState(new PaidState());

_repository.Save(order);

transaction.Commit();

}

}Transition Logging

You can have the Context log transitions for auditing and debugging. This gives you a complete history of state changes without touching the states themselves:

public class Order

{

private IOrderState _state;

private readonly ILogger _logger;

public void SetState(IOrderState state)

{

_logger.LogInformation(

"Order {OrderId}: {FromState} → {ToState}",

Id,

_state.GetType().Name,

state.GetType().Name

);

_state = state;

}

}Testing

Each state is a unit with clear boundaries:

[Fact]

public void DraftState_ReservesInventory()

{

var order = new Order { Id = "123", Items = items };

var inventory = new Mock<IInventoryService>();

var state = new DraftState(

validator, inventory.Object, repository, email);

state.Process(order);

inventory.Verify(i => i.Reserve(order.Items), Times.Once);

}Summary

The State pattern packages status-specific behavior into objects, letting an entity change how it acts when its internal state changes.

Remember Mario's power-ups: same buttons, different behavior depending on current form. That's the mental model.

The advantage: statuses become isolated and testable units, new ones mean new classes instead of longer if/else chains, and transitions are explicit rules rather than scattered conditions.

The cost: more classes to navigate and upfront setup.